Does it matter who owns a country's iconic brands?

A seismic shock in the coffee world - but who cares?

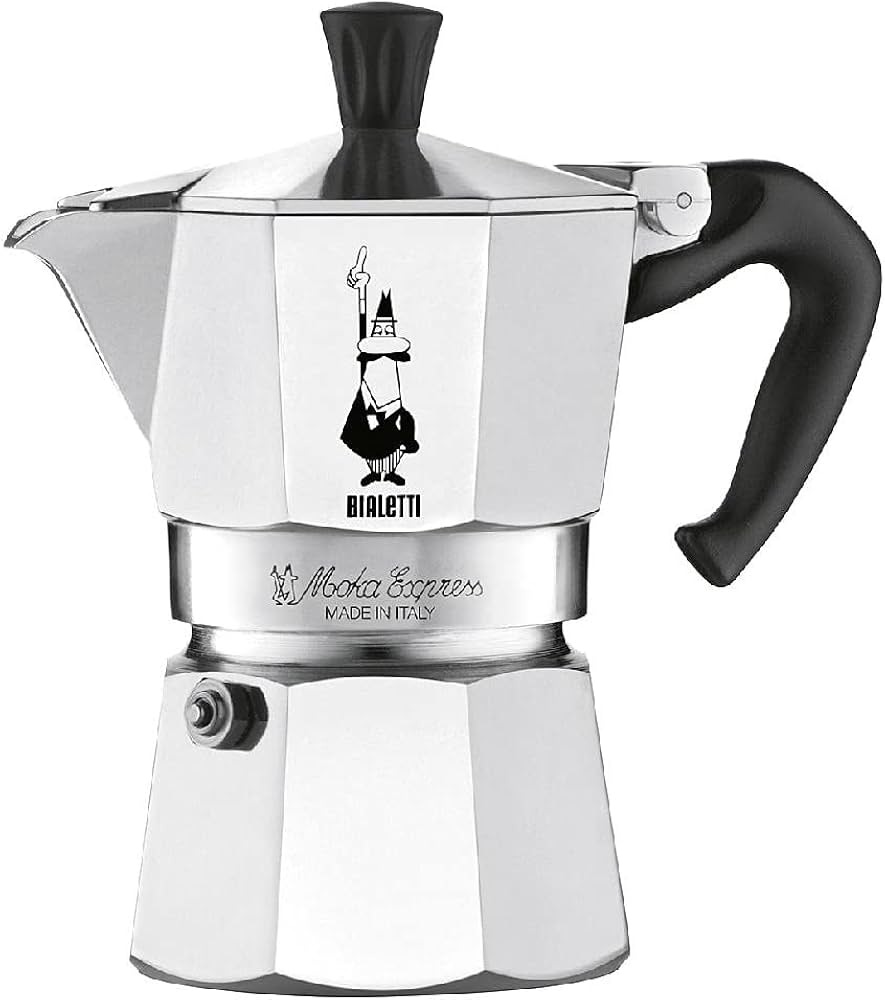

As the famous moka coffee pot manufacturer Bialetti, an icon for coffee lovers worldwide and quintessentially Italian, looks set to be acquired by a partly Chinese-owned company, does it matter who actually owns the shares?

Bialetti is said to be on the cusp of a deal with Nuo Capital, founded by Stephen Cheng, managing director of the World Wide Investment Company (WWIC) in Hong Kong.

The subject of home versus foreign owership causes heated debate in the UK, Europe and the US. Not least because embedded brands act as flag bearers for many groups who want to prove their political agenda. For nationalists especially, the fact that a brand can be bought and moved out of the country is often a clarion call for a sign that the country is in decline.

But does it matter if the company that makes wonderful Italian coffee pots is not Italian?

Brands are emotive things, but does the consumer really care, especially when the fuss has died down?

If you take the UK as an example, many iconic British brands are now owned by overseas companies.

Some notable examples include:

- Rolls-Royce and Mini cars (owned by German company BMW)

- Jaguar and Land Rover (owned by India's Tata Motors)

- Cadbury (owned by American company Mondelez International, formerly Kraft)

- Tetley Tea (owned by India's Tata Group)

- Harrods (owned by the State of Qatar)

- The Body Shop (recently sold to German private equity group Aurelius)

- Selfridges (now fully controlled by Thai retailer Central Group)

- HP Sauce and Weetabix (owned by American companies)

- Walkers crisps (owned by American company PepsiCo)

- Bentley cars (owned by Volkswagen)

- Kit Kat (Swiss-owned)

- Marmite (Dutch-owned)

- Newcastle Brown Ale (Danish-owned)

- Hamleys (Chinese-owned)

- The Financial Times (Japanese-owned)

A recent survey conducted by The Grocer and Nielsen found that of the 150 biggest grocery brands in the UK, only 44 were home-owned. Out of 91 brands created in the UK, only 36 were still owned by British companies.

In the manufacturing sector, foreign ownership rose from 25% to 40% between 2000 and 2007, measured in terms of output. Among larger companies, foreign ownership is now between 70% and 80%, with 2,000 firms taken into foreign ownership in just one decade. This trend shows no signs of slowing down.

In other words, a significant portion of UK infrastructure and top quoted companies are under foreign ownership.

While this foreign investment can bring benefits such as job creation and economic growth, it has also raised concerns about the loss of control over iconic British brands and industries.

Just exactly what "control" means is up for debate. It's clear that the ownership of companies working in defence, or advanced software, should arguably remain within their country's boundaries. Look at the fuss with ARM Holdings going to the US, but for everyday brands, does it really matter?

Arguably, the companies behind brands, many of the quoted, but even those in private hands, are constantly in play and that is a fundamental rule of capitalism and a result of globalisation. It would be tough and probably illegal for any democratic country to control the sales of companies and brands beyond the justification of national security, or naked protectionism.

Of course, it could come down to how respective new owners are to brands steeped in history. If they ride roughshod over tradition and years of customer engagement, it could backfire on the brand itself.

If they remain sensitive to their new brand's personality, maybe no one will even notice.